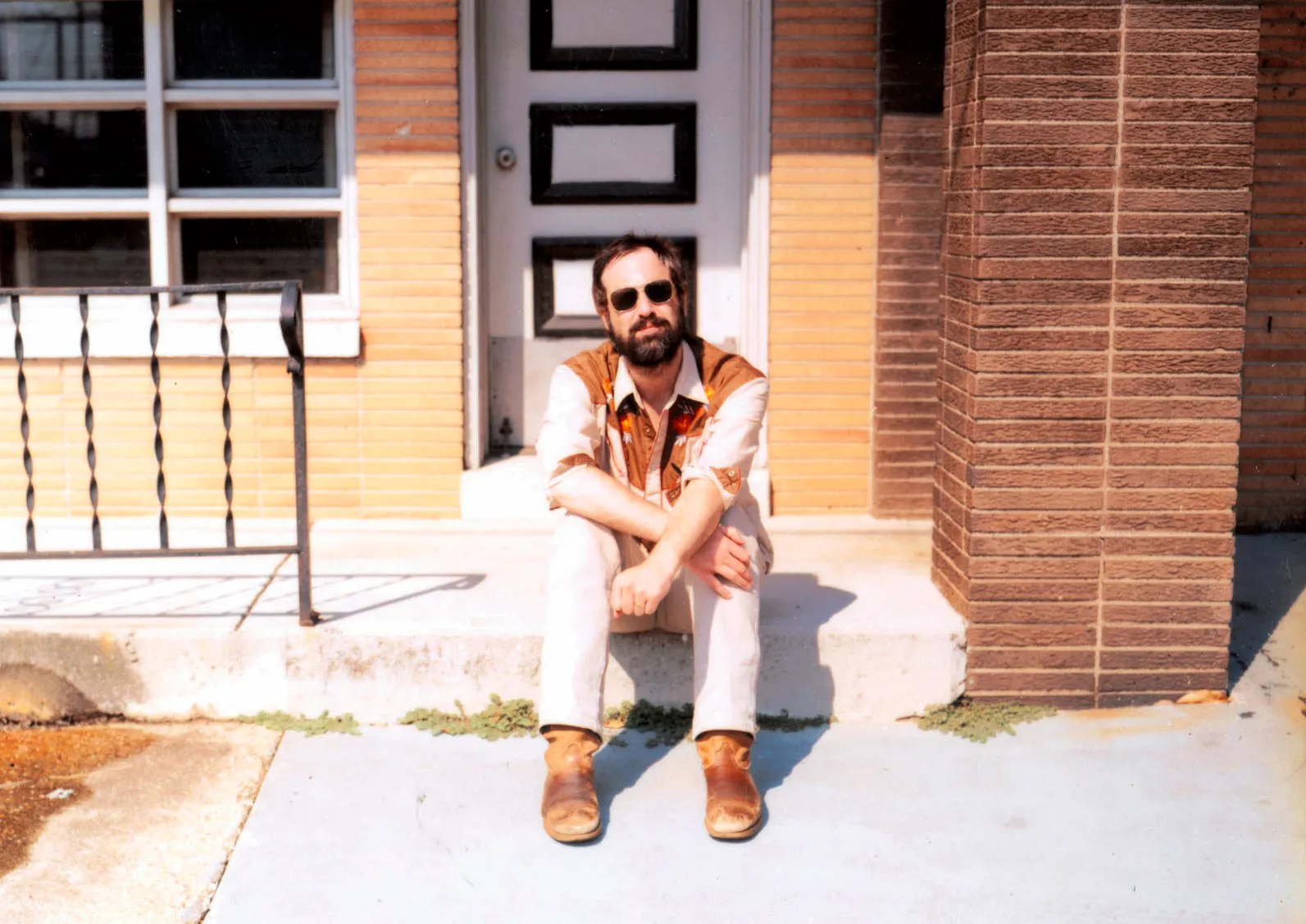

My dear friend Matt Neely introduced me to David Berman in the fall of 2003. Matt and I attended grad school together and one day he lent me his CD of the album Bright Flight, by Berman’s band Silver Jews. Their current Spotify bio describes them as “a beautiful mess of indie rock, country-rock and lo-fi with lyrics both witty and profound.” After a few listens I was hooked. Beyond the scratchy guitar rifts and straightforward, yet often fractured folk-rock melodies, I really connected with Berman’s songwriting and shaky vocals. He was a lyricist who could turn a phrase like no other. His crackly deadpan delivery only added to his effectiveness as a storyteller.

One of my favorite lyrics of Berman’s comes from his song “Time Will Break The World.” I repeat it to myself each year when winter grows long and I grow tired of yet another snowfall:

The snow falls down so beautiful and stupid

Couple this with Phil Connor’s prediction from Groundhog Day and you have perfectly summarized the late-winter, early-spring feels of Wisconsin.

Berman struggled with depression and drug addiction throughout his life. Tragically, he died by suicide in August of 2019, just one month after having released his first new music in a decade, under the new moniker Purple Mountains. A close listen to the self-titled album reveals a version of David Berman who was still very much struggling with his demons.

I had been planning on seeing Berman perform live for the first time later that summer. The news of his death shook me, as it did so many others. His impact was widespread, among fans and fellow musicians alike, and an outpouring of love and heartfelt condolence seemed to flow from every corner during the weeks to follow. In an article titled “David Berman Changed the Way So Many of Us See the World,” Mark Richardson writes:

It feels important to note that his lyrics, which seemed to be beamed in from another dimension, were used in service of songs that were generally sturdy and sounded good wherever they were needed.

Still, though, those words. Jazz critic Gary Giddins, writing about the work of Ornette Coleman, once noted ‘the music hits me in unprotected areas of the brain, areas that remain raw and impressionable,’ and Berman’s words functioned like that too. He had a gift for writing that, ironically, and in a very Berman-esque way, is hard to talk about. His use of language is so specific, it’s hard to find some of your own to describe it in a way that doesn’t diminish what you’re trying to convey. ‘The meaning of the world lies outside the world’ is how he put a related idea, in another context, in his song ‘People.’ But the way I’m describing it now makes it sound like something heady and tangled and complicated. It was the opposite. Berman had a knack for representing what was right in front of you in a way that made you see it as if for the first time.

I find myself relating to Richardson’s words, as I try to find the right words, to describe David Berman’s words. You’re better off just accessing his music directly. Even if Berman’s suffering was clearly expressed through his songs, he conveyed it in a tone that was both warm and oftentimes comical. There was a therapeutic lightness toward life’s difficulties that he wove into the fabric of his songs. It was a quality that I think genuinely helped a lot of people.

In another song touching on winter’s theme, “Snow Is Falling in Manhattan,” he writes the ghost of himself into the very song, allowing for visitors to gather round and warm themselves by the fire he creates:

Songs build little rooms in time

And housed within the song’s design

Is the ghost the host has left behind

To greet and sweep the guest inside

Stoke the fire and sing his lines

The song builds a room, presumably within a house, where the songwriter continues to live, and hosts whichever guest might appear with a need for warmth and companionship.

Berman wrote a book of poetry called Actual Air, originally released in 1999, but reissued in 2019, also just weeks before his death. As is the case with his songs, Berman’s witty insights about life, in all its wonder and bleakness, can be found in this brilliant collection of poems.

One of my favorites is “The Homeowner’s Prayer.” It’s a poem that considers the circular and linear nature of time. We move through the stages of life on a path toward our imminent demise, as the seasons continue to circle back around, obscuring the fact that one day they no longer will, at least not for us. And the time they take to come around seems to get ever faster as we get older. This is a sad poem about a man’s untaken opportunities and unlived experiences that are eventually lost to him. They were never really his to begin with because he did not live them. Time, as it were, passed him by.

But this poem reminds me that we ought to think of “home” as the people more so than the place. The title seemed incongruent to me at first, but maybe that is the prayer—let me value people above place. I have moved enough in my life to understand that my true home is the people I get to experience life with. Everything loses its flavor when you take away the people for whom you care about the most. We often confuse this simple truth in a modern society that confuses simple facts. What if, as a “homeowner,” the first thing that came to mind were the people who inhabit my heart, rather than the house I inhabit? Berman’s poem helps me to be mindful of the moments I get to spend with my people and to value the immaterial over the material.

I think David Berman knew that home was more than a place. He saw his own songs as a home, not just for him to live in, but also for any guest who would enter them to listen. Here is the poem in its entirety:

The Homeowner’s Prayer – by David Berman

The moment held two facets in his mind.

The sound of lawns cut late in the evening

and the memory of a push-up regimen he had abandoned.It was Halloween.

An alumni newsletter lay on the hall table

but he would not/could not read it,

for his hands were the same emotional structures

in 1987 as they had been in 1942.Nothing had changed. He had retained his tendency

to fall in love with supporting actresses

renowned for their near miss with beautyand coffee still caused the toy ideas

he used to try out on the morning carpools,

a sweeping reorganization of the company softball leagues,

or how to remove algae from the windows of a houseboat.He remembered a morning when the carpool

had been discussing how they’d like to die.

The best way to go.He said, why are you talking about this.

Just because everyone has died so far,

doesn’t mean that we’re going to die.But he had waited too long to speak.

They were already in the parking garage.

And now two of them had passed away.It was Halloween.

Another Pennsylvania sunset

backed down the local mountainspraying the colors of a streetfighter’s face

onto the narrative wallpaper of a boy’s bedroom.Once he thought all he would ever need

was a house with time and circumstance.He slowly made his way into the kitchen

and filled a bowl with apples and raisins.The clock was learning to be 6:34.

The willows bent to within decimals of the lawn.

It was Halloween.

The years go round and round. Halloween just passed and soon it will again. The 52 weeks that make up a year bring us back to this same spot pretty quickly. Add up a life’s worth and you only get 4,000 weeks, on average. How will you spend the time?